Perennial Grass Recovery And Animal Impact

It is with some reluctance that we write this article as this is a hotly con-tested area with many passionate advisors who all believe they are correct. This is an attempt to take a dispassionate, evidence-based view of the outcomes over time. As this is a complex area there is more than one answer so please check if the ideas work on your place before adopting.

Key Points:

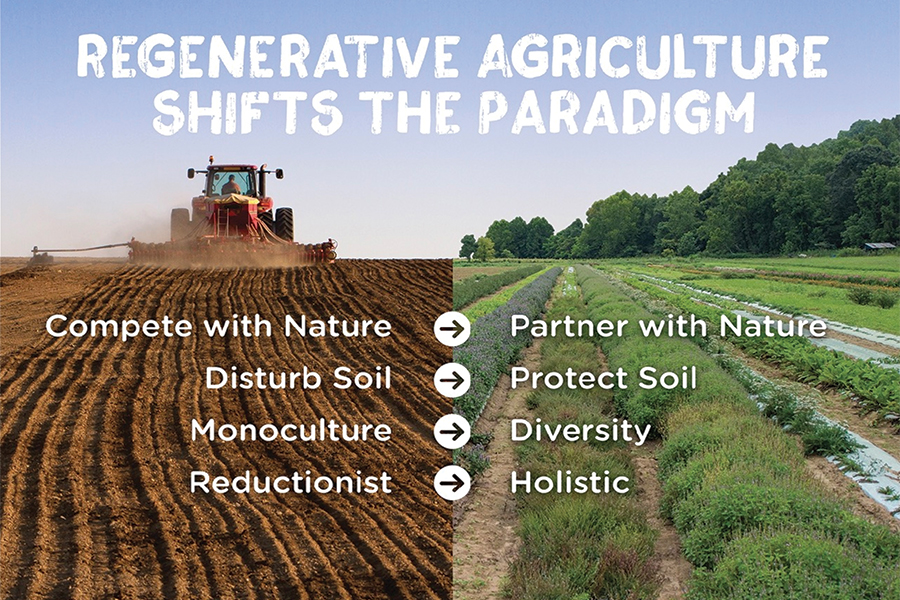

- Only management that increases landscape function and perennial grass quality/succession and diversity can be considered regenerative and reversing biodiversity loss.

- Majority of grazing advice does not include leaf emergence rate/perennial grass physiology and therefore fails over time.

- Research on animal impact/stock density thresholds that regenerate perennial grasslands is required on each farm.

Landscape Function And Perennial Grass Quality:

Grazing management has gone through many stages and cycles. This article is based on shifting to a highly dense, high successional, high landscape function predominantly perennial-based grassland. The management levels discussed are based on their ability to achieve this out-come at low risk and consistent profit.

The Stipa Action on the Ground Project in partnership with Sydney University proved that focusing on the above landscape description and using leaf emergence rate in the definition of perennial grass recovery massively increased landscape function in two years. We have found no research anywhere that shows that level 1 and levels 2 & 2A in Table 1 Grazing Descriptions, consistently increase landscape function, soil health while lowering rainfall risk.

Very little advice is trying to achieve high landscape function with the consequence being that external inputs in the form of feeding, fertilizers, herbicides and pasture re-sowing are eventually required.

What is poorly understood is that light grazing or only grazing 50% or top third etc. results in loss of the more palatable perennial grasses over time. The mechanism is that the better grasses are preferentially grazed and have more leaf removed than the average. When the animals return these plants are not recovered and are overgrazed, eventually to extinction. The basis of this incorrect advice is that removing more leaf reduces root mass and increases recovery as researched by Crider. This is true but is in isolation to what happens across a pad-dock and of little value in a diverse pasture. To maintain and increase higher successional perennial and diverse grasses requires high utilisation and long recoveries.

Leaf emergence rate of perennial grass

Perennial grasses can only maintain a maximum number of green growing leaves per tiller. The number varies by species, but the key is to go past this point, before adding stock so that you produce enough litter to cover the ground between the perennial grasses i.e. increase landscape function.

For perennial rye grass, this means grazing when 4+ leaves have emerged. Raw litter increases stability and water infiltration. When this litter is actively decomposing a large increase in nutrient cycling is produced. Livestock at high stock density press raw litter onto the soil surface so that it can be colonised by the soil biota to allow this decomposition to occur.

Please note the dairy industry worries that this litter is wasted feed and therefore provides advice to graze at the 2 ½ to 3 leaf stage. The unintended consequences of this advice are that animal health and fertility is poor due to excess non-protein nitrogen in young leaves. These pastures require large inputs and re-sowing on a short, regular basis as the perennial grasses have not replaced their root reserves before the next graze even though Figure 1 suggests they have.

Figure 1 – Diagram of leaf emergence and replacement of root reserves

Source: https://www.dairyaustralia.com.au/farm/feedbase-and-animal-nutrition/pasture/perennial-ryegrass-management

Please note following dairy grazing advice will reduce animal health, animal fertility, landscape function, waterway health and profit.

Animal impact/stock density thresholds

Animal impact as a tool (as described by Allan Savory and Jody Butterworth) is poorly understood and I will use some of Stipa’s work, Johan Zietsman’s book and Jaime Elizondo’s recent Facebook post to try and explain how this tool works and how to determine what your land needs. The Facebook post by Jamie Elizondo shows clearly that just providing recovery does not produce dense perennial grassland. Only after high animal impact and significant recovery did this landscape shift to a dense perennial grassland with high landscape function.

The amount of stock density required to create animal impact is high and can be very inconvenient and tiring. Automating the movement of stock with Batt Latches or similar is how a few are using this tool. A few are using herding or attractants to overcome the need for fencing to achieve high stock density.

Thresholds for land regeneration

The best way (first heard from Allan Savory) to demonstrate the stock density required to change behaviour and stimulate massive germination of perennial grasses is to get a group of people in a room and keep shifting them into ever smaller halves of the room until they are within each other’s personal space and then they get noisy (laughing and giggling) as they are uncomfortable.

Usually takes about 4-5 halving’s in most situations. This may help give you the idea of what is required to push livestock into each other’s space. The stock density threshold is determined though small practice areas as each land type, rainfall amount and pattern are different. We have found a step change increase in perennial grass germination between 500 – 1000 cattle/ ha or 5000 – 10,000 DSE/ha stock density and use similar fencing design to Gabe & Paul Brown see photo below.

Source: Gabe Brown, Livestock Integration presentation

Comparison of different grazing practices

Table 1 is an attempt to explain the differences in grazing practices. It is difficult to describe and represent the difference between the different grazing practices as there can be a fair bit of overlap. For example, good set stocking can produce more profits and a better environmental out-come than poor rotational grazing. Dairy grazing relying on nitrogen fertiliser has surprisingly come out lower than set stocking because in general it uses massive amounts of nitrogen fertiliser that reduces soil carbon and leaches nitrates into groundwater and waterways while not producing decomposing litter. The easy example is to think of what is happening in dairy areas in Australia and New Zealand. Most of the rivers in dairy areas are now unfit for human consumption/ drinking due to nitrate load.

Table 1 Grazing Descriptions

Both set stocking and rotational grazing have little link to perennial grass recovery (based on leaf emergence) and therefore fail over time. Dairy grazing uses leaf emergence rate but due to not wanting to ‘waste’ any feed it does not increase landscape function. This focus on short term ‘waste’ means that dairy farmers waste fortunes feeding, resowing pastures, fertilizing, battling weeds, bulk high milk cell counts, low cow fertility etc.

The large Caring for Country project, Communities in Landscape’s, regenerating the grassy box woodlands in New South Wales that Stipa was a partner in showed that thoughtful, low stocking rate, set stocking resulted in good biodiversity outcomes (many of the properties had no debt and were comfortable with lower stocking rates and lower risk producing regular consistent profit).

Full recovery planned grazing increases landscape function and perennial grass succession. Ecology research has long acknowledged the importance of perennial grass litter for nutrient cycling and soil stability. However, such works frequently demonise the presence of livestock and the productive use of these ‘natural landscapes’. As such, most of this research has been poorly integrated and utilised by agricultural scientists.

Conversely, top-tier agricultural research, typically funded by government organisations is still centred around a ‘productivity at all costs’ mentality, where production units indicate soil health. Landholders and the public are confused (and for good reason!) with resulting conflicting and incongruous land management advice. Adopting leaf emergence rate as a no-nonsense and unfakable grazing indicator for the wider pastoral sector may be the way forward.

The dairy community have shown this is an easy to use measure of pasture development stage, albeit to their own detriment, as we have previously described.

Grazing perennial ryegrass at the 4+ leaf stage (rather than 2.5-3) allows for the growth of litter, thereby enabling more effective nutrient cycling, replenishment of root reserves and long-term plant resilience.

Research and experience suggest that perennial grasses are recovered when they look like an ungrazed plant and contain fresh litter. This definition has been shown to rapidly increase landscape function on 12 farms within 2 years in the high rainfall zone (average seasons). This definition has proven to be a good early warning during dry seasons. On farm practice areas with a range of stock density and recoveries are required to determine the stock density that will be over the animal impact threshold that rapidly increases perennial grass density and diversity.

Responses