Weeds: Good or Bad?

Weeds: Good or Bad?

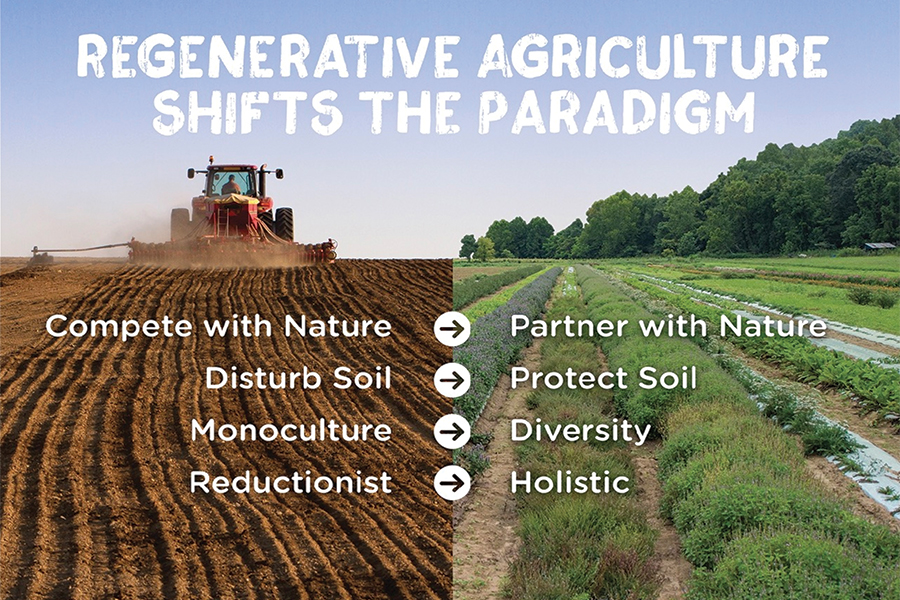

Many farmers see weeds as enemies—invaders that choke crops, take away soil nutrients and water and increase labor costs because of the need to get rid of them. The common refrain among farmers is that “weeds are sending us bankrupt,” as they constantly wage an ongoing war on these persistent plants. Yet what if they are trying to help you farm? With the advent of regenerative farming, many are starting to look a little closer, realizing that weeds may be telling us something deeper about the state of our soils and landscapes.

So are they good or bad?

Whilst weeds are a huge nuisance to many growers, weeds are also a natural response to disturbance. They emerge when soils are bare, compacted, or depleted—particularly after drought, fire or floods, functioning as early responders in ecological succession. As such, they are powerful indicators of soil health and land degradation, acting not only as a symptom of imbalance but as a tool for regeneration.

From an ecological standpoint, many weeds offer profound benefits. Deep-rooted varieties like dandelions and thistles penetrate compacted layers, helping to aerate the soil and improve water infiltration. As these plants break down, they return valuable minerals and nutrients to the soil surface, making them available for future crops. Others, such as capeweed or Patterson’s Curse, act as bioindicators—signaling low calcium or soil compaction and helping farmers make informed management decisions.

From an ecological standpoint, many weeds offer profound benefits. Deep-rooted varieties like dandelions and thistles penetrate compacted layers, helping to aerate the soil and improve water infiltration. As these plants break down, they return valuable minerals and nutrients to the soil surface, making them available for future crops. Others, such as capeweed or Patterson’s Curse, act as bioindicators—signaling low calcium or soil compaction and helping farmers make informed management decisions.

Beyond soil health, weeds contribute to biodiversity. Their flowers offer food for pollinators, and their structure provides habitat for insects, birds, and beneficial predators. Some weeds even support soil microbial life, fostering symbiotic relationships that enhance the resilience of cropping systems.

Weeds also play a practical role in erosion control. By quickly covering bare soil, they protect it from wind and water erosion, stabilizing fragile landscapes. In some cases, they even assist in phytoremediation—absorbing heavy metals and toxins from polluted soils, which would otherwise remain a danger to crops and groundwater.

Certain species offer medicinal and culinary value, too. Plants like purslane, nettles, and dandelions are not only edible but rich in nutrients, offering an untapped food source for both humans and animals.

Of course, unchecked weed growth can become problematic—especially when invasive species dominate and reduce native biodiversity or outcompete crops. But is the key eradication or understanding? By reading the signs weeds offer, farmers can work with nature rather than against it, using weeds as guides toward soil regeneration and healthier farm systems.

Of course, unchecked weed growth can become problematic—especially when invasive species dominate and reduce native biodiversity or outcompete crops. But is the key eradication or understanding? By reading the signs weeds offer, farmers can work with nature rather than against it, using weeds as guides toward soil regeneration and healthier farm systems.

In regenerative agriculture, the mindset shifts from domination to observation. Weeds become teachers. They point to compacted ground, low fertility, overgrazed paddocks, or imbalances in the soil food web. With this knowledge, farmers can adjust grazing patterns, improve compost practices, or plant diverse cover crops—reducing the conditions that allowed weeds to flourish in the first place.

In summary, weeds are not simply bad, they are ecological messengers. Their presence reveals the story of the land and its potential for healing. By embracing a balanced perspective on weeds, we not only reduce inputs and increase resilience but also move toward a deeper relationship with the soil beneath our feet.

Responses